Saudi-born, alUla-based multimedia sculptor Abdulmohsen Albinali explores themes including the loss of biodiversity and traditional practices, the merging of life and death, the politics of display, and the tension between artificial and organic in his artworks in a number of ways, notably with the use of plant matter, found objects, ceramics, digital animation, and, as discussed here, taxidermy. In his experimental practice based in anthropological and cultural research, Albinali explores “a variety of different subject matter…driven by an inherent fascination with the natural world. The resulting work investigates the correlations between the collective perception of nature and our place within it.”

On 3 November 2024, L.E. Brown speaks to Abdulmohsen Albinali via video chat from her home in California, USA, while he is conducting an arts and research residency in Madrid, Spain.

✹✹✹

LE Brown: I’d love to start our conversation by discussing the work you’re doing that incorporates taxidermy. Tell me about the use of this medium in your practice.

Abulmohsen Albinali: My use of taxidermy touches on a few things. Taxidermy is meant to fool viewers for a moment when it’s posed like a living animal; once you come closer, you realize the creature is quite still and dead. Your brain, on an instinctual level, reacts to this illusion in a strange way, questioning its own instincts.

This questioning then relates back to folklore and the loss of biodiversity—central themes across my practice, which go hand-in-hand. Folklore and traditional practices are being lost at a rapid pace, just like biodiversity. And this is true anywhere you go, considering current industrial late-stage capitalism. There is a worldwide uncertainty which surrounds these traditions and lifeforms.

At a personal level, I’m interested in sharing, reinterpreting, and dissecting Saudi and Arabian oral traditions and folklore stories. I’m ultimately a sculptor, so I work to translate these traditions and stories into tangible works of art. But, even while we make these translations, the question becomes: will these traditions and stories become obsolete? For example, if you write down an oral tradition, it loses its initial form, and is no longer an oral tradition. I want to question how we articulate these stories.

With taxidermy, I resurrect items and animals that have become obsolete and present them as if they are artifacts in a museum. I try to intervene on the actual shape of the animal, treating it like a distinct tool and extension of the institution, museum, or archive. At their core, I want these installations to feel like they’re scientific objects, presented in a museum as a type of mythical, metaphysical archaeology.

LEB: It comes down to disrupting how we are expected to record and present history. Oral tradition plays such an important role in society, but the only institutional alternative that seems to be proposed is to write down the traditions. With digital technology, we can capture and interpret them in new ways, but it isn’t always considered valid. So to interpret oral histories in a way that isn’t strictly textual is a very exciting and important movement.

AA: One of the inspirations I draw from is an exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian focusing on First Nations people which was curated based on their Indigenous stories and knowledge. There was contemporary art mixed with historic artifacts, but it wasn’t done in an occidental or western way of categorizing nature, and instead represented their existing beliefs and understandings.

Another inspiration of mine is the Haida tribe in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. They outlawed writing because they realized it would cause their oral tradition to disappear. So they refused to use it, rejecting writing and reading to keep their traditions alive.

LEB: I feel like the archiving of the near future, especially alongside your use of taxidermy which you mentioned as a reinterpretation and optical illusion, coincides with the digital technology you use in your artworks. Your videos and stop motion graphics present these histories in a wholly new way, or at least in a way that hasn’t been done widely.

AA: As a child in the 90s, I grew up visiting museums and became used to seeing these scientific animations recycled from the 60s and 70s—very traditional scientific museum displays. Across my work, I try to interpret the qualities and fixtures that I find interesting in museum display. I try to deconstruct the idea of the museum and question how it communicates with me and what modes of communication I am drawn to. Like, for example, how taxidermy has been used in traditional, scientific, museum dioramas.

Traditional installations like that require you to move in a very specific way and experience the display in narrow-minded terms. You have to stand in a certain position to understand its very objective context, presented right in the center. From that angle, it’s meant to help you imagine the subject’s environment or time. That is something I build upon with my video work and taxidermy installations—it leads back to the idea of the diorama.

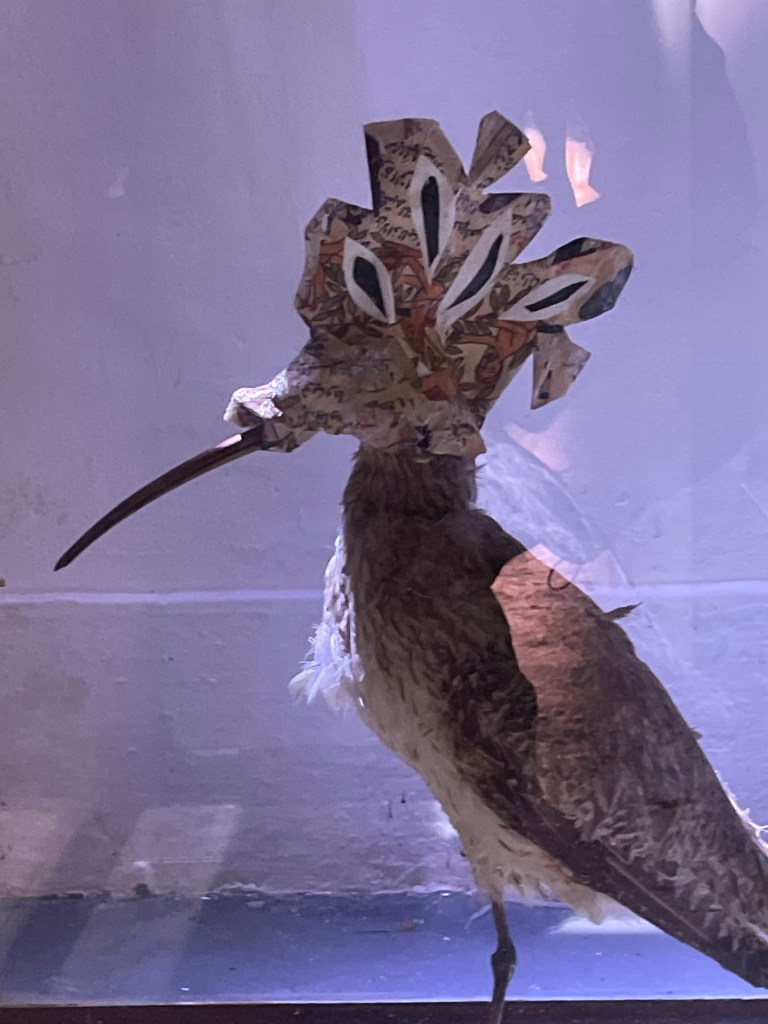

LEB: The concept of the diorama is so tied to the politics of display and the politics of looking and seeing, as well as the reverse wherein the visitor is seen by the artwork and the artist is imaged in the creation itself. This is especially relevant to your installation featuring the chimerical bird posed in a glass vitrine. Can you elaborate on that artwork?

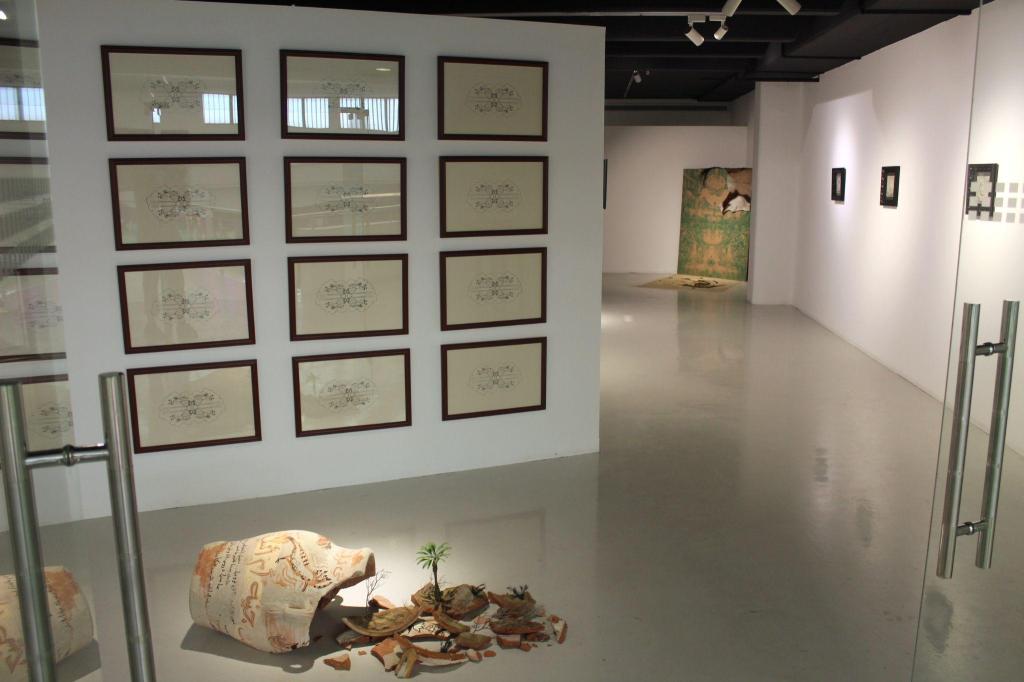

AA: That work was part of a wider concept called The Museum of Folklore, which really calls into question our point of view. It explores the dichotomy present in folklore; on one hand, it’s a means of collective memory and needs to be preserved, but on the other, it’s constantly retold and shifting. All of the surrounding elements, like individuals with different perspectives living in different times and locations, affect the story and mutate it. It’s a continuous mutation.

To make this artwork, I couldn’t present myself as an objective observer or an archivist, because, at the end of the day, I needed to own up to the idea that these stories are being told through my perspective. I’m inevitably going to speak about them the way I want to, and discuss them from my own point of view, so it can’t be some idealized treasure that I hold on to. The end result tries to lose that aspect.

For this project, I created a shifting display, because it’s different each time I install it. Things are pulled out, things are put in place differently or in different ways. In that way, you have a similar mutation of the project, just like folklore.

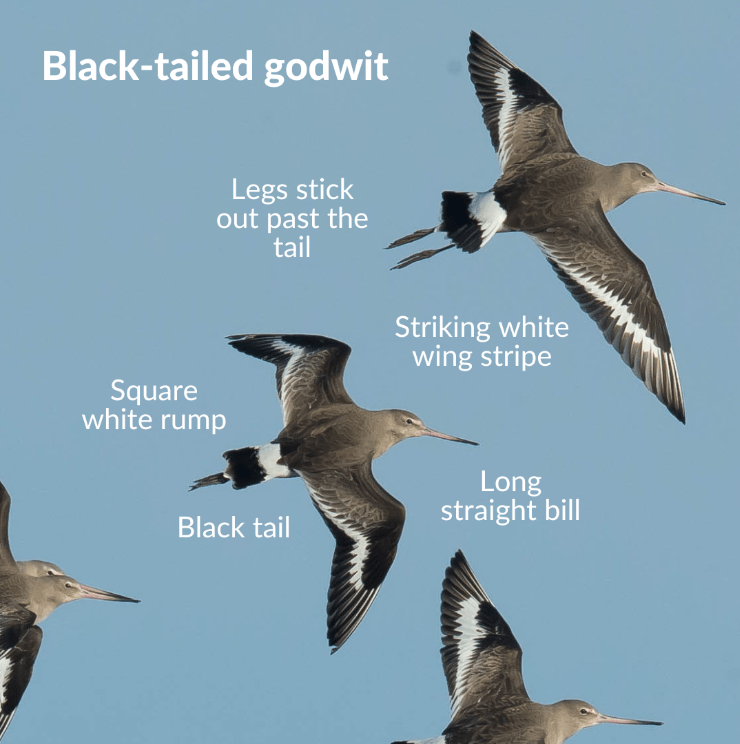

The bird itself is mutated, too. The bird’s body, a black-tailed godwit, connects to a head that’s a collage, made of paper and PVC glue.

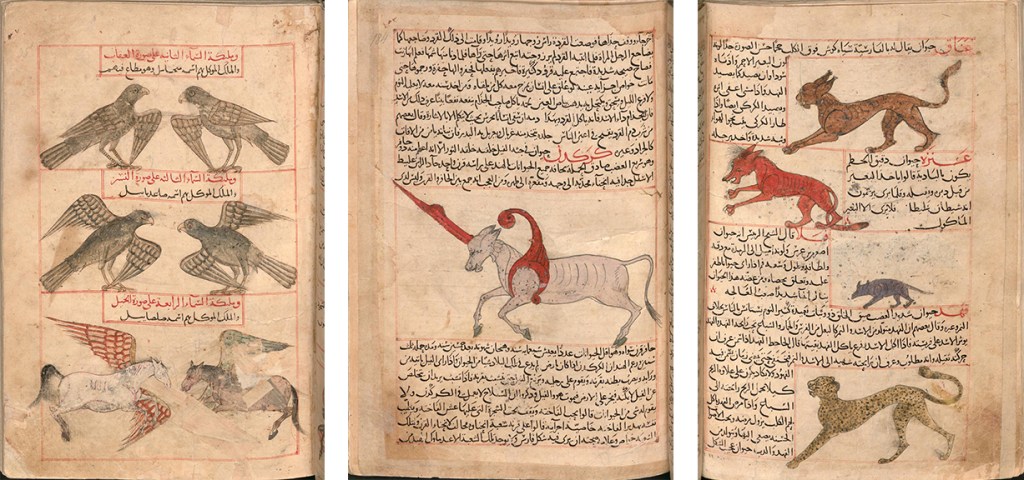

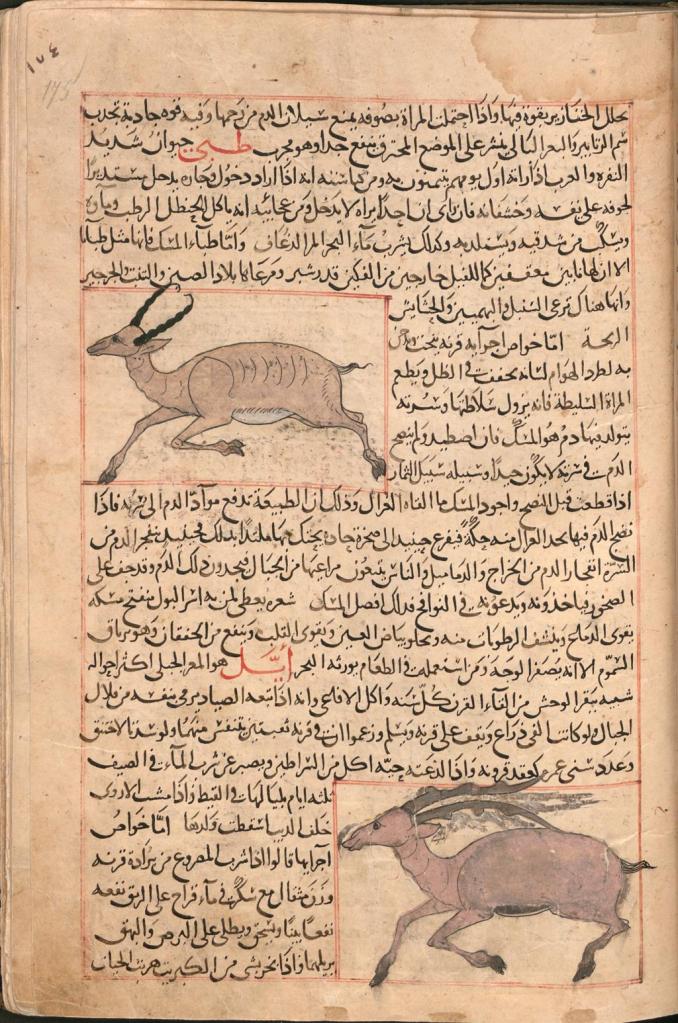

For that, I took inspiration from the book The Wonders of Creation by Persian author Zakarīyā Ibn Muḥammad al-Qazwīnī (c. 1203-1283) which is considered one of the first sci-fi books. In the book, he categorizes animals and plants in a very matter-of-fact way, but categorizes djinn and mythical creatures alongside them. He documents them as if they’re just regular creatures that exist. I tried to do the same—create an animal that’s both mythical and real.

The bird’s collaged head has been changed to that of a hopi or hoopoe, which is a bird I show in the film at the end of the exhibition. When you walk through the exhibition, you see animal remains and the bird in the vitrine, all of which indicate you’re seeing something of the past.

The video installation that you face at the end of the exhibition connects everything in the story. It ties together all of the elements and characters and you get to experience a path I create, a story, which gives them a new meaning and narrative. Then you get to expand on that, experiencing it again in a new way.

LEB: And the exhibition itself becomes an artwork, something that results in multiple ways of seeing, disrupting the diorama tradition of needing to experience it from one sightline.

Regarding the bird’s collaged head—why the hoopoe?

AA: The hoopoe was a point of interest because of its story told throughout history. It was said to be the messenger between Sheba and Solomon, and I was immediately attracted to the fact that this bird was a storyteller. It felt connected to Hermes, or Mercury, who was the messenger for the gods and the first to know the news from Olympus and pass it down. So it became a story of a bird that tells a story.

In other works, I’ve focused on other birds, like the bulbul bird in the 2024 film I made titled The Dreamer Dreams. And I’ve focused on other stories of birds as storytellers, like the Jeddah version of Cinderella, whose name was Zaynab. Instead of a fairy godmother, she had a bird who was her guide, who gave her information and support along the way. This bird was a supporting character but no one is shocked that the protagonist is talking to a plant or bird. Stories like those give us an understanding of history’s acceptance of the natural world and our relationship with it.

LEB: In this diorama, the taxidermy/collage bird is housed in a very traditionally western museum vitrine. Where did you source the vitrine, and what is it made of?

AA: I found that in a flea market as well, actually. It is a traditional display and I felt like it was exactly the type of cold, scientific museum display I had seen growing up. The museum, as a concept, has a lot of baggage, especially regarding decolonization, reappropriation of artworks, looted art and objects, excluding narratives from different cultures. So why can’t a museum also be personalized? This is a work-in-progress for me, built on a wanting to recreate the museum in a decolonized, less occidental way. This is a journey I’m going on with my research.

LEB: In the vitrine, I love that its nails are exposed. With these long nails jutting out of its sides, it feels like something that is ready to self-destruct, like it’s at its own end.

AA: It relates back to decay. In thinking about small historic museums where the collection is collecting dust in a single room, crammed together, we have to question the state of these objects, and if they’ll mutate as well.

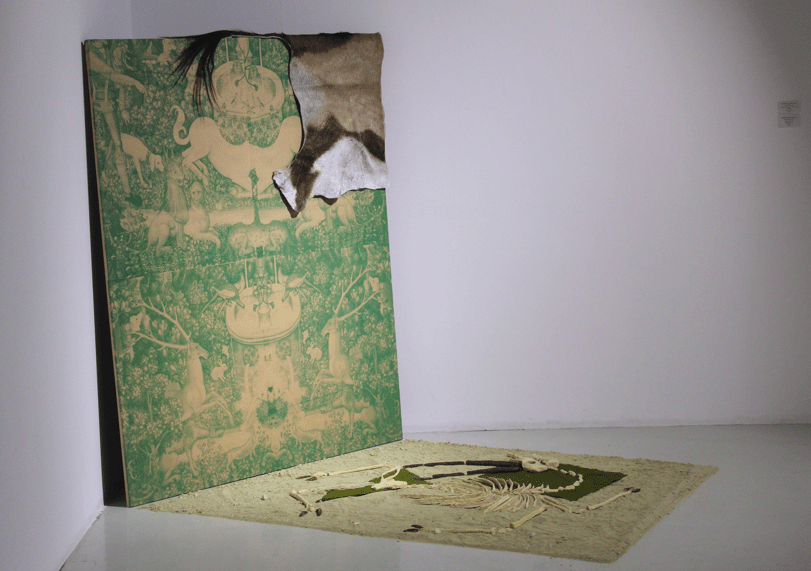

LEB: There are two more artworks that really spoke to me regarding their relationship to taxidermy. One features a rug of animal skin laid out on top of an array of tiles in conversation with the video artworks behind it. The other actually relates due to its lack of taxidermy and animal matter, and focuses on the skeletal remains of an animal on a bed of sand. Can you tell me more about those works?

AA: They’re kind of similar to each other in terms of content, which is similar to creating a connection between folklore and nature. Back to the idea of stories and how they mutate, I wanted to look for a story from the region that I found interesting in terms of that scope of movement. I learned that in the early 20th century, the oryx nearly went extinct and was only preserved in some small areas of the Gulf. There’s a distinction between the African and Arabian oryxes and the Arabian ones were critically endangered.

The World Wildlife Fund started contacting private collectors and began to export remaining oryxes in Europe and America back to the Gulf. Their successful breeding program was the first to bring an animal back from extinction. In the 70s, these animals were shipped back to Saudi and the Gulf to repopulate the desert, and most of the oryxes you see today are descendants from those bred in the west.

So there was a traceable movement, basically a migration, to and from the western hemisphere, ending up back in nature. This idea was very interesting to me—getting back to nature.

The animal skin here belonged to a colonial hunter and collector from Rhodesia [now known as Zimbabwe], which I found at an estate sale. He had so many dead animals in his collection. The oryx here isn’t an Arabian oryx—which are illegal to have—but connects to how these animals, including this one, were hunted nearly to extinction.

The skin is on top of a group of tiles which depict the story of a girl who is running for her life, being chased by a monster, and she comes to a tree. Instead of climbing it, she asks the tree’s permission first. She wants its consent, letting it say yes, you can climb me. This, to me, says a lot about the relationship we used to have with nature, and then how that relationship died.

I set the installation up to look almost like stage props, as I like the idea of world-building. It’s meant to create a world and take you somewhere. So I created this collection of aged tiles that feel like they could be from ruins like Pompeii, with images fading and pieces broken. The physical and metaphorical layers of this piece touch on the two things I’m trying to discuss: folklore and nature.

LEB: I love that you bring up stage props and world-building because this vignette here, the tiles underneath the skin rug backed by the videos, makes you feel like you’re taken back to a historic environment—part way between when fur rugs were made from necessity and when they became a status symbol. It brings up binaries like local and foreign, natural and synthetic, hard and soft, created versus found, and makes us see they’re all one and the same.

AA: When people come into the room, I want them to feel like something was lost. Almost like a crime scene that occurred long before anyone visits the installation, like it’s too late. It’s kind of cynical, but also a very urgent thing, and a sign of our times.

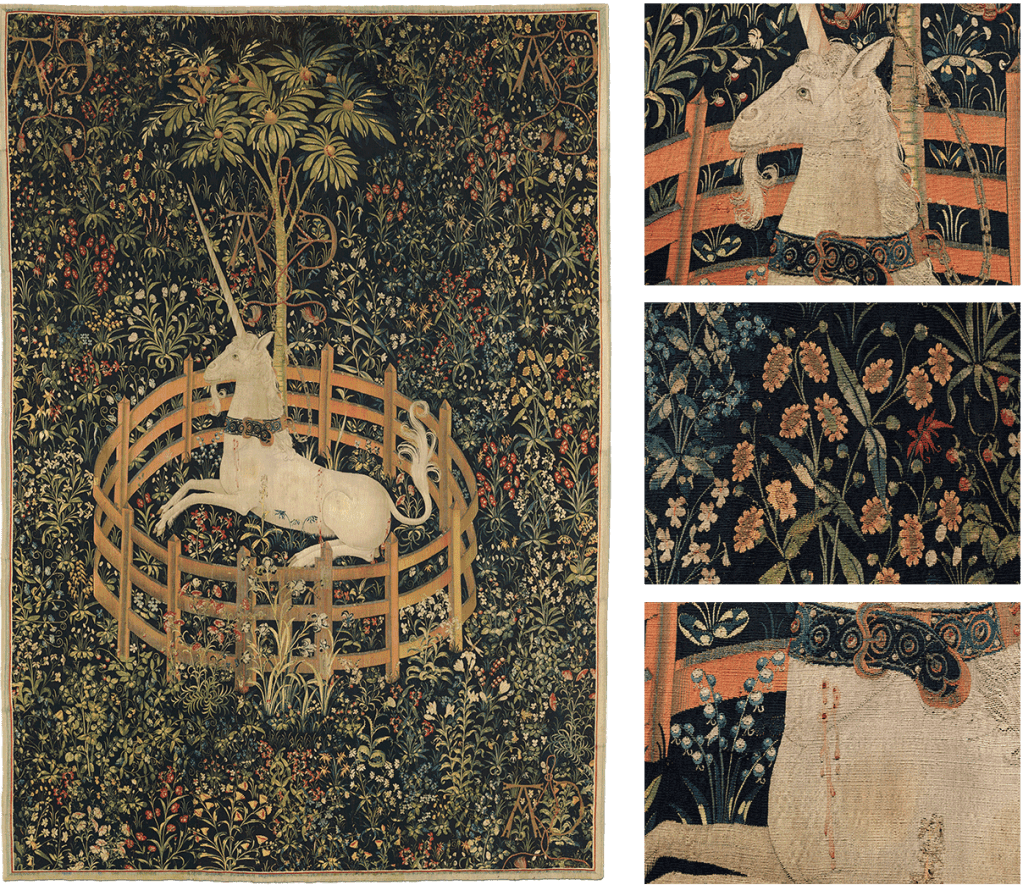

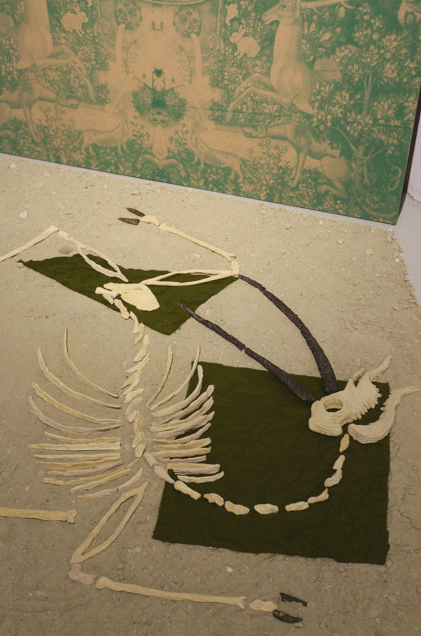

The other artwork, with the clay bones, was inspired by The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, originally from the Netherlands and now living in the Met Cloisters. This is also connected to the story of the oryx because in Europe, oryx horns were sometimes sold as unicorn horns. The animals were sometimes even mistaken for unicorns. I love that this Arabian animal, tied to this romantic idea of the Arabian desert, mutates into a mythological horse-like creature in another part of the world, even becoming an allegory for Jesus. I even included a small bit of oryx skin in this installation, too.

The installation of ceramic bones also, to me, felt directly related to this idea of world-building and bringing you back to the past. These are the first things that you’ll find when you dig a hole in an archaeological site: ceramics or pottery, and bones. It becomes both a bed and grave for the oryx as well as the unicorn, which, in folklore, was similarly hunted to extinction. So it’s funny that the real self and the mythological self faced the same demise. These creatures are so different, but their journeys share so many of the same paths.

LEB: And it comes back to these ideas of binaries like real and fake, natural and synthetic, true and false. Like how unicorns seem like such a plausible creature whereas animals like giraffes, or two-headed lambs, which actually exist, seem so absurd. Obviously these aren’t real unicorn bones, so what are they made of?

AA: They’re oven-baked ceramic. It’s very much part of my prop-building or world-making, to make them seem realistic.

I want the bones on the floor and the tapestry behind them to act like two parallel doors—they’re facing each other, almost becoming each other’s shadows, but one is real and one is not.

These fakes or illusions, like metaphors and fantastic creatures, are used as a way to process big life questions and mitigate stories where you can discuss deeper things, like trauma and other aspects of life where the harsh reality is simply too harsh. So you can use these creatures and monsters to soften the story and entertain while you teach someone an important lesson. Then, in the 20th century, folklore died as an educational tool, and has been replaced by the modern educational system. It connects, again, in saying that folklore is dying as it’s no longer a functional mainstream tool for knowledge.

LEB: Mythology and folklore is, and has always been, such an important way to rationalize and explain things we don’t understand, and using those explanations to teach us lessons. This relates again to the disruption of modern history recording and archiving—it feels important and timely to disrupt these traditional notions and understandings of history, of teaching, and of museums and other institutions.

AA: And it relates back to how you can tell a story in its original version, but it’s never going to be the full narrative. Maybe you’re discussing, for example, a plant from a scientific point of view, but this plant exists within generational knowledge for another people, or has a significant meaning. So all of these different perspectives can expand on the scientific story and make it more holistic. That’s how the inside of a museum should look—shared experiences in one space.

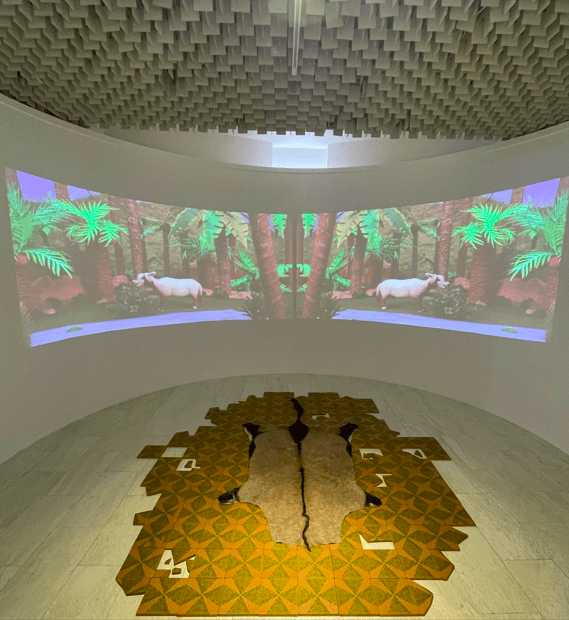

LEB: Do you mind elaborating on the digital video that’s playing behind the installation featuring the oryx skin?

AA: This is a stop motion film titled Can You Hear the Djinn in the Trees? which originally played in the Museum of Folklore, which is juxtaposed with the installation to show a hoopoe and an oryx which dies in the film. It creates a connection between the objects in the exhibition but also the different narratives that are present in these stories. I wanted to show that they’re not always consistent—over generations, they mutate.

I wanted to play with this idea in the film and bring you to a mythical Khaleeji Valley, a long time ago. You are observing the scene as a viewer and you are able to follow the character around. But a second character comes in, and the narrative shifts, and you leave the first one to follow them around instead. It’s an inconsistent narrative that actually has two separate endings. But, at every point, it acts like a diorama for the work. It’s curved, so it envelopes you in the scene.

LEB: I like the idea of the video installation taking up space as if it were a diorama. If you place your face right in front of a diorama, it completely fills your vision—much like facing these screens. The installation becomes immersive, and is an experience in and of itself.

It also relates back to the artworks and the installations living multiple lives, and it makes us question how we’re witnessing what we see in front of us in these art institutions, both historic and contemporary.

AA: In this work, you have two films mirroring each other, side-by-side. They’re exactly the same until the last minute, where you get to see the two different endings. It adds up to the idea of how one can articulate a tradition that has multiple versions. It was important to me to show how something was interrupted. And, in that way, you create these two unique paths so you can choose which to follow. You end up having a say in the ending.

LEB: It’s so cyclical—that again returns to the idea of reconstructing how we keep or archive history; like, as we’ve said, from an occidental or western standpoint, history has to be kept static, written in stone. There’s no alternative for multiple endings or understandings and there’s only one truth, whereas oral histories and visual representations can have so many outcomes that are specific to each of us. In the western world, we can’t necessarily understand or accept these different realities that are all contemporaries within the same story, within the same narrative.

Aside from these works, are there any other artworks you’ve made which utilize taxidermy?

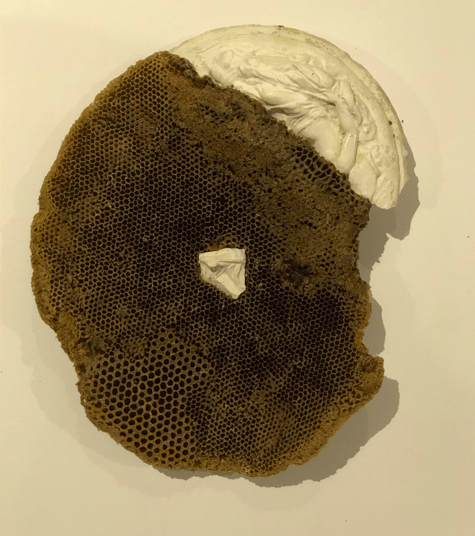

AA: Other than those, I’ve made a lot of sculptural works with organic materials including moss, shells, and beehives. I started collecting beehives I found around my house, which were emptied because of Colony Collapse Syndrome. I began to look at these hives like they were lost civilizations. It looked to me like they could have been an abandoned Roman city with falling buildings and structures. I began to merge those with pieces of plaster that I felt also reflected shapes from antiquity, and from there, made a small series of works. Together, they feel like clues towards answering some of life’s elusive mysteries.

✹✹✹

Leave a comment